By Jorge Ramos

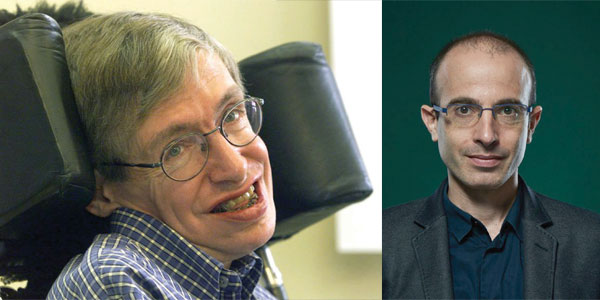

If I were to suggest two books to read this year, they would be “Brief Answers to the Big Questions,” by the renowned cosmologist Stephen Hawking, who died in 2018, and “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind,” by the historian Yuval Noah Harari. Both present lucid insights into what might happen after we die and the stories we tell ourselves to explain why we die.

“Do I have faith?” asks Hawking, who could only communicate using his facial muscles due to a progressive motor neuron disease, in his book. “We are free to believe what we want, and it’s my view that the simplest explanation is that there is no God,” he writes. “No one created the universe and no one directs our fate. This leads me to a profound realization: There is probably no heaven and afterlife either.”

Hawking argues that “the universe was spontaneously created out of nothing, according to the laws of science” in “an event we now call the Big Bang” and, therefore, no divine explanation for our existence is needed.

Billions of years later, after the planet presented the necessary conditions for the emergence of life and, eventually, of humans, we started searching for explanations. And this is where Harari’s insights into the wonderful history of humankind begins.

Harari explains that we have invented many myths and legends in an attempt to explain everything that happens to us, and this is precisely what defines us and sets us apart from other animals. “This ability to speak about fictions is the most unique feature of Sapiens language,” writes Harari. “It’s relatively easy to agree that only Homo sapiens can speak about things that don’t really exist, and believe six impossible things before breakfast. You could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven.”

Harari contends that it is this collective imagination that enables us to believe in “common myths” and allows strangers to cooperate successfully with each other, which is “why Homo sapiens came to dominate the planet.” This is precisely what separates us from bees, ants and chimpanzees.

In the future, Hawking predicts the rise of “superhumans.” He proposes that humankind is entering a new phase of “self-designed evolution,” in which we will be able to change and improve our DNA in order to become more intelligent and less aggressive, and resist the diseases that kill us.

At first glance, this seems like something to look forward to. If cancer, diabetes, sclerosis and heart disease could be eradicated, we could live longer and considerably improve our quality of life. Still, this kind of genetic engineering, this ability to tinker with our DNA, could cause a great division among humankind.

“Once such superhumans appear,” Hawking writes, “there are going to be major political problems with the unimproved humans, who won’t be able to compete. Presumably, they will die out, or become unimportant. Instead, there will be a race of self-designing beings, who are improving themselves at an ever-increasing rate.” Once life expectancy is longer, Hawking suggests, the human race will be able to colonize other planets.

He also predicts that while laws will likely be passed against genetic engineering, the temptation will be too hard to resist. This, of course, sounds rather troubling, like a delirious science-fiction scenario. Both Harari and Hawking are extraordinary examples of scientists who never stop asking questions and are not afraid to posit what some answers might look like.

Hawking, who died at age 76, also humbly reflects on the meaning and purpose of his life in his book: “I don’t have a grudge against God,” he writes. “I do not want to give the impression that my work is about proving or disproving the existence of God. My work is about finding a rational framework to understand the universe around us. For centuries, it was believed that disabled people like me were living under a curse that was inflicted by God. Well, I suppose it’s possible that I’ve upset someone up there, but I prefer to think that everything can be explained another way. …”

Both these books offer, without a doubt, another way of looking at the big questions.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

El Cielo y los Superhumanos

Si sólo hubiera podido leer dos libros en el año que pasó, escogería “Breves Respuestas a las Grandes Preguntas”del recientemente fallecido cosmólogo Stephen Hawking y “Sapiens; Una Breve Historia de la Humanidad” del historiador Yuval Noah Harari. Ambos enfrentan con lucidez el asunto de qué ocurre cuando nos morimos y las historias que nos inventamos.

Me temo que no les tengo muy buenas noticias.

“¿Tengo fe?” se pregunta Hawking, quiens vivió con una discapacidad causada por una progresiva degeneración de los nervios y sólo se podía comunicar con sus músculos faciales. “Todos somos libres de creer en lo que queramos, pero desde mi punto de vista la explicación más sencilla es que Dios no existe. Nadie creó el universo y nadie dirige nuestro destino. Esto me lleva a una profunda conclusión: Probablemente no hay un cielo, ni vida después de la muerte.”

Hawking argumenta que “el universo fue creado espontáneamente de la nada, de acuerdo con las leyes de la ciencia” en “un evento que ahora llamamos el Big Bang” o una gran explosión y que, por lo tanto, no hay en esto ninguna explicación divina.

Millones de años después, cuando la tierra generó las condiciones necesarias para tener vida inteligente, los humanos empezamos a buscar explicaciones. Y ahí es donde entra Harari, con su maravillosa historia de la humanidad.

Nos hemos inventado muchos mitos y leyendas para tratar de explicar lo que nos pasa. Pero esto es precisamente lo que nos define y diferencia de otros animales. “Esta capacidad de hablar sobre ficciones es la característica más singular del lenguaje de los Sapiens”, escribe Harari. “Es relativamente fácil ponerse de acuerdo en que sólo el Homo Sapiens puede hablar sobre cosas que no existen realmente, y creerse seis cosas imposibles antes del desayuno. En cambio, nunca convenceremos a un mono para que nos dé un plátano con la promesa de que después de morir tendrá un número ilimitado de bananas a su disposición en el cielo de los monos.”

Harari asegura que esta capacidad de imaginarnos cosas colectivamente, de tener “mitos comunes” y de cooperar entre extraños “es la razón por la que los sapiens dominan el mundo.” Eso nos separa de abejas, hormigas y chimpancés.

Quien se imagina un futuro muy distinto, con “superhumanos”, es Hawking. Él asegura que la humanidad está entrando a una nueva etapa de “evolución auto-diseñada” que nos permitiría modificar y mejorar nuestra carga genética para hacernos más inteligentes, menos agresivos y evitar las enfermedades que nos matan.

Esto, de entrada, no le sonaría nada mal a muchos. Sin cáncer, diabetes, esclerosis y enfermedades del corazón podríamos vivir muchos años más y mejorar considerablemente nuestra calidad de vida. Pero esta ingeniería genética, reparando nuestro ADN, podría generar una grave división en la humanidad.

“Una vez que estos aparezcan”, escribe Hawking, “van a existir muchos problemas políticos con los humanos que no se han podido mejorar (genéticamente) y que no pueden competir. Ellos podrían morir o perder importancia. Y, en cambio, habría una raza de seres auto-diseñados que se mejorarían con gran rapidez.”

Con una mayor expectativa de vida, asegura Hawking, se podrían colonizar otros planetas. Pero esto, por ahora, suena a preocupante y delirante ciencia ficción. El mismo científico adviertió que, seguramente, se implementarán en el futuro leyes en contra de la ingeniería genética en humanos. Aunque la tentación, dice, es muy grande.

Tanto Harari como Hawking son extraordinarios ejemplos de científicos que preguntan incansablemente sin temer a las respuestas. Hawking, quien murió en el 2018 a los 76 años de edad, reflexionó con humildad sobre el propósito de su vida. “No tengo ninguna pelea con Dios”, escribió. “No quiero dar la idea de que mi trabajo es probar o negar la existencia de Dios. Mi trabajo es encontrar un marco racional para entender el universo que nos rodea. Por siglos se creía que gente con discapacidad como yo sufríamos una maldición enviada por Dios. Bueno, es posible que yo haya molestado a alguien allá arriba, pero prefiero pensar que todo se puede explicar de otra manera…”

Estos dos libros son, sin lugar a duda, otra manera de preguntar.