Estamos atorados. Es casi medianoche y hay más aviones llegando al aeropuerto de la ciudad de México que puertas para recibirlos. Esperamos media hora en un avión que no se mueve, otra media hora en un camioncito que no llega a ninguna parte y una hora más haciendo fila y pasando migración y la aduana. Aprieto un botón. Es verde. Oigo: “Pase”. Hace frío y es de madrugada, pero no importa. Ya llegué.

Más que otros años, me urgía regresar a México, aunque fuera un ratito. A ver a mi mamá, a mis hermanos y a la ciudad que dejé hace casi 33 años.

La nostalgia empieza por la boca: Me atasco de tacos al pastor, de huevos a la mexicana, de caldo de camarón, de Churrumais, de galletas Marías con mantequilla de La Abuelita, de leche fría con Chocomilk — el de Pancho Pantera. Era mi menú de niño. Hoy es la comida reconfortante del que regresa (aunque duela la panza).

Esos olores y sabores me regresan a un México que ya no existe pero que traigo arado como rayitas en mi memoria. Proust a la mexicana. Las pláticas están salpicadas de qué fue de fulano y de zutano, o de quién vive ahora en “nuestra casa”. Sí, nuestra casa.

Uno de mis hermanos saca una foto de su celular. Ahora nuestra casa está pintada de amarillo y alguien mandó cortar el árbol de la entrada. Nuestra casa es, desde luego, donde crecí durante casi dos décadas — en Bosque de Echegaray en el estado de México — y que dos décadas atrás vendieron mis papás. Pero esa es la casa que mi alma — cualquier cosa que eso sea — reconoce como propia, no la otra veintena de casas y apartamentos que he habitado en Estados Unidos.

Los que podemos, regresamos a nuestra casa (donde quiera que esté, al menos una vez al año). De preferencia en Navidad y Año Nuevo. Esta vez, quizás, muchos regresan con más alegría que antes porque Donald Trump, quien se está postulando por la nominación republicana para presidente, nos quiere hacer la vida imposible a los inmigrantes en Estados Unidos. Su mensaje de odio se ha extendido en las encuestas, en las redes sociales y en las bocas amargas que ahora se sienten con la libertad de insultar igual que la del copetón.

Yo voy y vengo. Mi vida — ese tinglado compuesto por hijos, trabajo, sueños, inversiones y amores — está bien anclada en Miami. Miami — una generosa y cambiante ciudad poblada en gran medida por gente que no nació ahí — es mi segundo hogar. A los hispanos en Miami, dice un buen amigo, nos tratan como a ciudadanos de primera. Es cierto. Nadie se siente extranjero en “Mayami”.

Pero muchos mexicanos ya se cansaron. Se cansaron en Chicago y en Houston y en Los Ángeles y en “Puebla York” de chambear y chambear por años y de seguir igual de lejos del sueño americano — esa mezcla de casa bonita, trabajo decente, buena escuela para los niños y la promesa de que mañana las cosas van a ser mejor. Y por eso se están regresando a México para no volver.

Por primera vez desde la salvaje operación “Wetback” en 1954, más mexicanos se están yendo de Estados Unidos que los que están llegando. Del 2009 al 2014 se regresó un millón de mexicanos a México, según el centro Pew, y sólo vinieron 870 mil mexicanos a Estados Unidos. Es decir, ahora hay 130 mil mexicanos menos en Estados Unidos.

Trump está muy equivocado. No hay una invasión mexicana a Estados Unidos. Pero Trump, es de todos sabido, usa el miedo para ganar votos.

A pesar de la narcoviolencia en México, de la corrupción oficial y de un presidente que sigue escondido, muchos inmigrantes están regresándose a México. ¿Por qué? Por falta de oportunidades económicas en Estados Unidos, por un creciente clima antiinmigrante y por las deportaciones. Y también porque en México no hay ni Trump ni terrorismo.

Me trepo a otro avión y, una vez más, me siento dividido. Dejo a unos en México pero otros me esperan en Miami. Y me doy cuenta que, en el fondo, soy de muchas casas y de muchos lugares. Así nos toca a los inmigrantes. De pronto, recuerdo a Isabel Allende y me tranquilizo. No hay que escoger entre un país y otro, me dijo, se puede ser de los dos.

Cierro los ojos y trato de hacer la paz conmigo mismo mientras el avión, suave pero inevitablemente, se levanta.

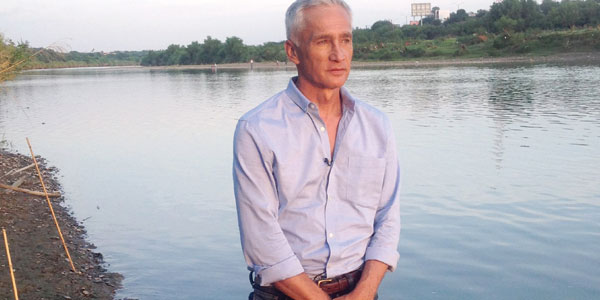

(Jorge Ramos, periodista ganador del Emmy, es el principal director de noticias de Univisión Network. Ramos, nacido en México, es autor de nueve libros de grandes ventas, el más reciente de los cuales es “A Country for All: An Immigrant Manifesto.”)

(¿Tiene algún comentario o pregunta para Jorge Ramos? Envié un correo electrónico a Jorge.Ramos@nytimes.com. Por favor incluya su nombre, ciudad y país.)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Going Home

By Jorge Ramos

We’re stuck. It’s almost midnight, and Mexico City’s airport doesn’t have enough gates to accommodate all the flights that are landing. So we wait: a half-hour in an airliner at a standstill, then another half-hour in a small bus, then an hour in line at customs. By daybreak, there is a chill in the air. But it doesn’t matter. I’m finally home, for a little while — to see my mother, my siblings and the city I left almost 33 years ago.

Those of us who can go home to Mexico from the U.S. do so at least once a year, preferably around Christmastime or for New Year’s. This year in particular, world events have made all of us more conscious of just where home is.

Whenever I visit Mexico City, familiar flavors and aromas are the first things that spark my nostalgia. I binge on tacos, Mexican-style eggs, shrimp broth, Churrumais snacks, Marias cookies with La Abuelita butter, glasses of cold milk mixed with Pancho Pantera’s Chocomilk powder. These were all my favorites growing up. Today, they are comfort foods for those of us who return to visit — and they always bring back a Mexico that only exists in my memory.

The conversations with my family are full of reminiscences — “what happened to what’s-his-name,” and so on. Our talk eventually turns to who might now be living in “our house.”

One of my brothers pulls up a photo on his phone. It’s of our old house in Bosques de Echegaray, in the State of Mexico, where we grew up. Our parents sold the house many years ago, and it’s now painted yellow. I notice that the old tree at the entrance has been removed. It’s still our house; the one that my soul — whatever that is — acknowledges as my home.

Now my life is anchored in Miami, my second home — a generous, multicultural city that is mostly populated by people who were born elsewhere. As a good friend often points out, Hispanics in Miami are treated as first-class citizens. He’s right. Nobody is an “alien” in Miami.

But many Mexicans, documented or not, who are living in other parts of the U.S. — in Chicago, in Houston, in Los Angeles, in New York — are simply exhausted. They scrape by for years, doing jobs that Americans won’t, yet they remain far from achieving the American dream — a nice house, a decent job, good schools for their children and the promise that things will be better tomorrow.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump, who is running for the Republican nomination for president, seems intent on making the lives of all immigrants miserable, and his messages of hatred and fear have only increased his popularity. And his anti-immigrant rhetoric is repeated constantly on social media.

For the first time since the “Operation Wetback” program of 1954, more Mexicans are leaving the U.S. than entering. According to research from Pew, from 2009 to 2014, 1 million Mexicans returned to Mexico, while 870,000 came to the U.S. This means that there are about 130,000 fewer Mexicans living here than there were a few years ago.

Yet Trump likes to talk about a Mexican invasion, even though he is very mistaken. Of course, it won’t matter to him — Trump will continue to use fear as a strategy to win votes.

Many immigrants are returning to Mexico for good, despite the drug-related violence and public corruption that plague the nation, and the failure of leadership from a president who prefers to hide from his problems. The lack of economic opportunities in the United States, coupled with an anti-immigrant sentiment is becoming too much to bear.

At the end of my recent visit to Mexico, I boarded another plane and again felt torn. Yes, I was leaving loved ones behind in Mexico, but others were waiting for me in Miami. Home for me is not one but several places. That’s what it means to be an immigrant.

The celebrated author Isabel Allende once pointed out to me that immigrants don’t have to pick between one country or another.

They can belong to both.

(Jorge Ramos, an Emmy Award-winning journalist, is the host of Fusion’s new television news show, “America With Jorge Ramos,” and is a news anchor on the Univision Network. Originally from Mexico and now based in Florida, Ramos is the author of nine best-selling books, most recently, “A Country for All: An Immigrant Manifesto.” Email him at jorge.ramos@nytimes.com.)