No hay mucha duda de que la imagen de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe es sinónimo de México. El sacerdote católico romano Prisciliano Hernández Chávez ha dicho: “Sin la Virgen de Guadalupe dejaríamos de ser mexicanos”. Por lo tanto, para dar a conocer la historia y la imagen de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe es estudiando la historia mexicana – que por ningún motivo un tema simple. En su estudio académico de la Virgen de Guadalupe llamado Mexican Phoenix, el historiador de la Universidad de Cambridge, David Brading, aborda la compleja historia sobre la profesa aparición de la virgen María a Juan Diego en diciembre de 1531 en el cerro del Tepeyac en el centro de México.

De acuerdo con Brading, el primer relato publicado de la historia de la Virgen de Guadalupe apareció en 1648 con el tratado de Miguel Sánchez “Imagen de la Virgen María, Madre de Guadalupe”. “Sánchez era dinámico tanto como por sentimiento patriótico como por el religioso”, declara Brading, “y toda su preocupación era demostrar que la iglesia mexicana le debía su fundación a la intervención directa de la Madre de Dios”.

Sin embargo, Brading declara que el trabajo de Sánchez no creó devoción hacia la Virgen de Guadalupe, debido a que su escrito ya había sido precedido por la devoción popular en la forma de una nueva capilla que ya había sido construida en el Tepeyac, y que pronto recibiría una atractiva actualización.

“Tal fue la explosión de fervor que en 1695 -1709 se construyó una majestuosa nueva iglesia en el Tepeyac, una construcción que en escala y esplendor rivalizaba a todas las más grandes catedrales de la Nueva España”, explica Brading.

Fue en medio del contexto sociohistórico de esta nueva España, el cual combinó los mundos de Europa, una civilización pasando por nuevos cambios radicales en medio de una reformación protestante y el surgimiento del secularismo, y México, una nueva civilización conquistada con una rica historia, que surgió el relato de la aparición.

“Mucho se ha dicho sobre las raíces prehispánicas de la participación nativa para el culto de la Virgen de Guadalupe”, explica Brading, “pero poca evidencia ha sobrevivido sobre la perdurabilidad de cualquier imagen prehispánica de Tonantzin en la mente y corazones de los nativos”, agrega Brading refiriéndose a Tonantzin, una diosa nativa venerada por los mexicanos nativos en el Tepeyac.

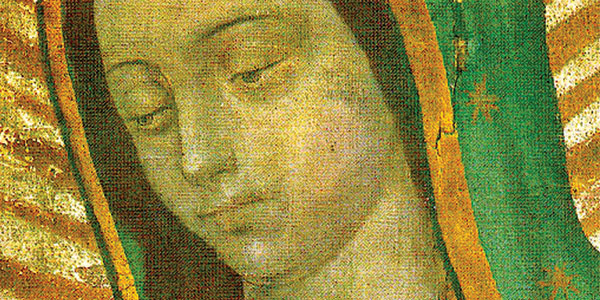

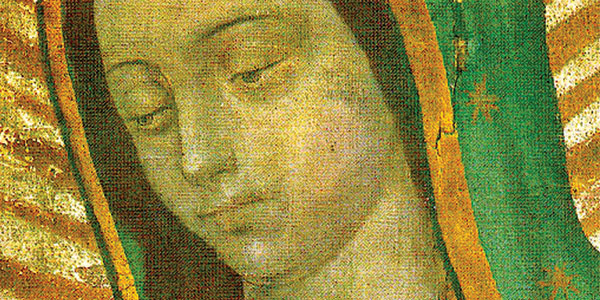

Y así, el escenario es establecido para trazar un poco las controversias alrededor de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Algunos dicen que Juan Diego nunca existió; otros dicen que la imagen fue pintada por manos humanas. Estos temas serán explorados en futuros artículos. Sin embargo, una cosa es segura, la imagen de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe tiene un significado especial para México y más.

Our Lady of Guadalupe: Myth or Fact?

By Nicholas Peterson

There can be little doubt that the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe is synonymous with Mexico. The Roman Catholic priest Prisciliano Hernández Chávez has said “Without Guadalupe we would cease to be Mexicans.” To study the story and image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, therefore, is to study Mexican history–by no means a simple subject.

In his scholarly study of Guadalupe called Mexican Phoenix University of Cambridge historian David Brading tackles the complex history surrounding the professed appearance of the Virgin Mary to Juan Diego in December 1531 at the hill of Tepeyac in central Mexico.

According to Brading, the first published account of the Guadalupe story appeared in 1648 with Miguel Sánchez’s treatise “Image of the Virgin Mary, Mother of Guadalupe.”

“Sánchez was animated as much by patriotic as by religious sentiment,” Brading states, “and his whole concern was to demonstrate that the Mexican Church owed its foundation to the direct intervention to the Mother of God.”

Brading claims that Sánchez’s work did not create devotion to the Guadalupe, however, because his writing had already been preceded by popular piety in the form of a new chapel that had already been constructed at Tepeyac and was soon to receive a handsome update.

“Such was the explosion of fervour that in 1695-1709 a majestic new church was constructed at Tepeyac, an edifice which in scale and splendour rivalled all but the greatest cathedrals of New Spain,” Brading explains.

It was in the sociohistorical context of this New Spain, which combined the worlds of Europe, a civilization undergoing radical new changes amidst the Protestant Reformation and rise of secularism, and Mexico, a newly conquered civilization with a rich history, that the account of the apparition emerged.

“Much has been made of the pre-hispanic roots of native participation in the cult of Guadalupe,” Braiding explains, “but little evidence has survived of the perdurability of any pre-hispanic image of Tonantzin in native mind and hearts,” Brading adds, referring to Tonantzin, a native female deity revered by native Mexicans at Tepeyac.

And so, the stage is set to trace a bit of the controversies that surround Our Lady of Guadalupe. Some claim that Juan Diego never existed; others that the image was painted by human hands. These topics will be explored in future articles. One thing is for certain, however, the image of Guadalupe holds special meaning for Mexico, and beyond.