By Jorge Ramos

“Between you and me there’s nothing personal.”

— Armando Manzanero

Presidents, former presidents and other politicians with even the slightest semblance of authority don’t like to be questioned. These people have let power go to their heads; they can’t even imagine that they might be wrong or that they should be held accountable.

Such leaders often think there are only two kinds of people in the world: those who are loyal, and those who betray them. When their power falters, they immediately assume there is an international conspiracy against them; that people are secretly plotting their downfall, or employing the most astonishing technological advances to make them look bad.

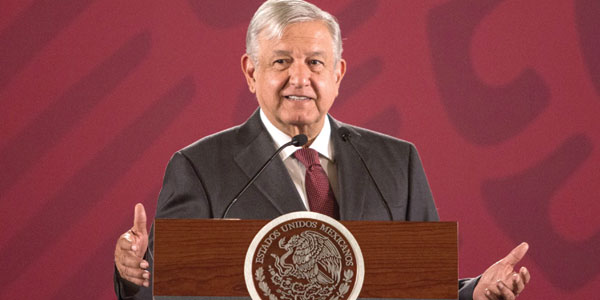

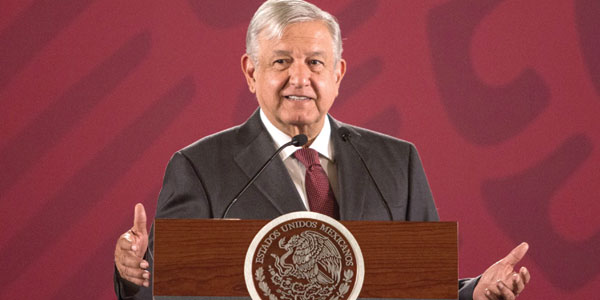

You see this everywhere — in the United States, with President Donald Trump; in Mexico, with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (or AMLO, as he’s known); and in Bolivia, with former President Evo Morales.

When these leaders have felt threatened, they have often directed their anger at independent journalists. But Trump, AMLO and Morales have to remember one thing: media scrutiny is nothing personal; it’s the job of journalists to act as counterweights to those in power. In the age of the internet and social media, few governments have the power to completely control the flow of information among and between citizens. This means that now, more than ever, challenging those in power ought to be standard practice. Trump, AMLO and others of their ilk better get used to it.

All this reminds me of a recent interview that Evo Morales gave in Mexico City. Gerardo Lissardy, the BBC journalist conducting the interview, dared to challenge the former Bolivian president, and Morales was clearly uncomfortable with the questions: How would you define your current position? Would you call yourself president, former president, ousted president or someone granted political asylum? Would you agree that there were irregularities in the election of Oct. 20? Didn’t you make any mistakes? Why didn’t you go to Venezuela instead of Mexico? Do you expect to return to Bolivia on a specific date?

Instead of answering Lissardy’s questions, Morales chose to condemn and discredit him: “I wouldn’t want to think that you seem to be talking on behalf of the Bolivian right-wing,” he said, and later “ … Even if you were my ideological and political enemy, I would never want to see you dead,” and “ … You’re not conducting an interview, but an ideological debate.”

Then Morales made the deluded and laughable accusation that Lissardy was actually having his questions texted to him during the interview: “Someone is telling you what to ask. I know these kinds of journalists. They’re telling you what to ask.”

Lissardy, startled, then had to explain: “No, no one is telling me anything. My cellphone is in airplane mode. There is no connection. These are the questions I have written down here.”

Could Morales really think people wouldn’t have legitimate questions about his nearly 14 years in power? Did he really think, against all logic, that BBC editors in London were telling their colleague in Mexico what questions to ask, in an effort to make Morales look bad?

The president of México, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is a lot like Morales: He hates tough questions. When Spanish reporter Silvia Chocarro asked during a recent news conference if he would agree to “refrain from using stigmatizing language against journalists and journalism,” the president replied that he wanted to stigmatize corruption, not journalists, and that he has “respect for every person.” He neglected to mention the time he called reporters the “fifí press” (the “posh media”), or that time he denounced reporters he didn’t like as conservative, looking only for bad news and taking things out of context.

AMLO has also said of journalists: “They bite the hand that took off their muzzle.” He seems to have trouble understanding how many Mexicans have died, or how Mexico remains one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, and the very serious concerns surrounding the recent appointment of the head of Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission. The primary task of journalists is to hold him accountable, not to support his “Fourth Transformation” project.

In any case, there is another president who has an even thinner skin in the face of media scrutiny. That would be Trump. Long a proponent of the notion of “fake news,” he applies the term to any information — or journalist — he doesn’t care for. His disputes with The New York Times, The Washington Post and CNN, to mention just a few news outlets, have been epic. He apologizes for nothing. His self-image is divorced from reality: He describes nearly everything he does in bloated superlatives, and he himself as a “very stable genius.”

Someone like this, lacking even the slightest sense of humility or humor, will never accept questions from a journalist.

That’s why Neil Cavuto, a host at Fox News, sent a message to the U.S. president after he criticized Chris Wallace, one of Cavuto’s colleagues. Cavuto reminded Trump that journalists are not required to praise him. On the contrary, Cavuto said, they “are obligated to question you and always be fair to you … even if it risks inviting your wrath.”

Asking tough questions is what journalists do. It’s true that sometimes we may seem confrontational, or even to be part of the political opposition. But challenging the powerful is our job. It’s nothing personal. It’s too bad Morales, AMLO and Trump can’t understand that.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Nada personal

“Entre tú y yo no hay nada personal”.

— Armando Manzanero

A los presidentes, expresidentes y hasta a los políticos con un poquito de autoridad no les gusta que los cuestionen. El poder se sube rápido a la cabeza y no se les ocurre que pueden estar equivocados o que alguien los obligue a rendir cuentas. A veces dividen el mundo entre leales y traidores. E inmediatamente piensan en conspiraciones internacionales, en intentos para derrocarlos y en las más alucinantes operaciones tecnológicas para hacerlos ver mal. Pasa en todos lados. Y lo sufren por igual los Presidentes de Estados Unidos y México, Donald Trump y Andrés Manuel López Obrador, que el expresidente boliviano Evo Morales.

La razón de su enojo suelen ser los periodistas independientes. Pero no es nada personal: una de las misiones del periodismo es, justamente, ser un contrapeso al poder.

Gracias a internet y a las redes sociales ya quedan pocos gobiernos sobre la tierra que pueden censurar e imponer sus contenidos sobre la población. Así que cuestionar a los poderosos es lo normal. Más que nunca. Ojalá se vayan acostumbrando.

Esto me recuerda una reciente entrevista a Evo Morales en Ciudad de México. Evo se veía molesto. El periodista de la BBC —una gran institución con una bien ganada reputación de integridad y credibilidad— lo estaba cuestionando y, claramente, no le gustaban las preguntas: “¿Cómo se define usted en este momento, presidente, expresidente, presidente depuesto, asilado político?, “¿usted reconoce que hubo irregularidades [en las elecciones del 20 de octubre]?”, “¿usted no cometió ningún error?”, “usted ha dicho en el pasado que quien se va de Bolivia es un ‘delincuente confeso’”, “¿por qué no fue a Venezuela en lugar de venir a México?”, “¿tiene fecha para volver a Bolivia?”.

Pero, en lugar de contestar las preguntas, Evo decidió criticar y descalificar al periodista, Gerardo Lissardy: “No quiero pensar que usted parece representante de la derecha boliviana […] Por más que seas mi enemigo ideológico y político, jamás querría verte muerto […] Con usted no es una entrevista, es un debate ideológico”. Y, luego, en un momento surrealista y ridículo, Evo acusó al periodista de estar recibiendo las preguntas por su teléfono celular. “Te están dictando para que preguntes. Yo conozco a esa clase de periodistas. Le están dictando qué van a preguntar”, le dijo Evo. A lo que Lissardy, sorprendido, tuvo que explicar: “No, nadie me está dictando. Está en modo avión el teléfono. No está conectado con nada. Estas son mis preguntas que tengo escritas aquí”. ¿Acaso nunca se le ocurrió a Evo Morales que hay preguntas legítimas sobre sus casi 14 años en el poder? ¿De verdad cree Evo en la absurda idea de que alguien en la BBC de Londres le estaba diciendo qué preguntar a su corresponsal en México con la intención de desprestigiarlo?

Al presidente de México, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, tampoco le gusta que lo cuestionen. Cuando la periodista española, Silvia Chocarro, le preguntó en una de sus conferencias de prensa si se comprometía a “utilizar un lenguaje que no estigmatice a los periodistas y al periodismo”, AMLO contestó que él quería estigmatizar a la corrupción “no a los periodistas” y que siempre actuaba “con respeto a todos”. (Excepto, claro, cuando llama a los reporteros “prensa fifí”, cuando los acusa de ser conservadores, de buscar lo podrido y de sacar las cosas de contexto.)

“Le muerden la mano a quien les quitó el bozal”, también dijo AMLO en referencia a los periodistas. Pero el Presidente de México parece no entender que hay muchos muertos en el país, que la nuestra es una de las naciones del mundo más peligrosas para ejercer el periodismo, que la nueva titular de la Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos fue elegida con serios cuestionamientos y que el trabajo fundamental de los reporteros es obligarlo a rendir cuentas, no apoyar su proyecto de la “cuarta transformación”.

Pero, sin duda, el mandatario que tiene la piel más delgada en su trato con los periodistas independientes es Donald Trump. Él ha popularizado el término fake news o noticias falsas y lo aplica a cualquier información o periodista que no le guste. Sus peleas con The New York Times, The Washington Post y CNN, entre muchos otros medios, son épicas. Nunca lo he escuchado disculparse por algo. Suele decir que todo lo que hace es lo más grande, lo mejor y que nunca se ha visto algo similar. Y tiene una autoimagen tan desproporcionada que, en una ocasión, en una de sus frecuentes sesiones públicas para hablar de él mismo, se describió como un “genio muy estable”.

Alguien así, sin una pizca de humildad ni sentido del humor, nunca va a aceptar que un periodista lo cuestione.

Esto llevó a que Neil Cavuto, uno de los presentadores de la cadena Fox News, le enviara un mensaje al Presidente estadounidense después de que éste criticara a uno de sus colegas, Chris Wallace. Los periodistas, dijo Cavuto, no están obligados a halagarlo; en cambio, están “obligados a cuestionarlo y a ser justos con usted … incluso si al hacerlo se corre el riesgo de ser atacados por usted”.

La naturaleza misma del periodismo es cuestionar. A veces, claro, da la impresión de que se trata de una confrontación y hasta de oposición política. Pero ese es nuestro trabajo: hacer preguntas difíciles a figuras públicas. No es nada personal. Lástima que Evo, AMLO y Trump no lo entiendan así.